On Wednesday 15 January, Lee and I continued our helo bonanza by flying to Cape Bird AWS. Just like Tuesday, the purpose of this trip was to check on the AWS and make sure things looked ok. Before flying to Cape Bird, there are a few important considerations the helo operations personnel have to consider.

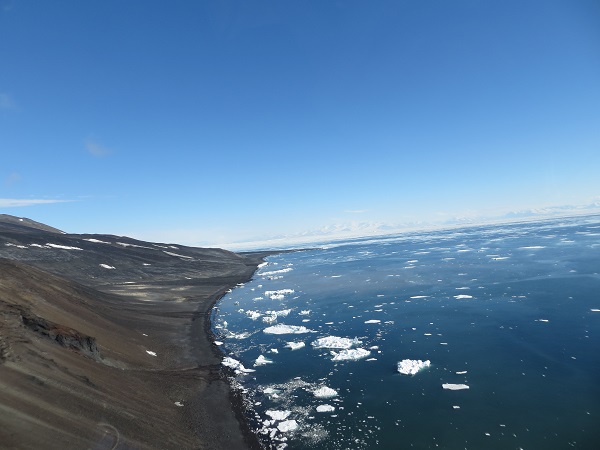

Cape Bird is at the northern end of Ross Island, while McMurdo is at the southern end. The helo cannot fly over open water, so it either has to fly over land or ice. This is important to keep in mind, especially this time of year, because at Cape Bird the sea ice breaks up and melts, leaving open water in its wake. There are also a few areas on the island along the route that are no-fly zones, due to penguin rookeries. Ross Island becomes more narrow, and essentially becomes a peninsula, as you approach Cape Bird. Consequently, there is only a thin flight path. If there is enough cloud cover that makes it difficult to see land, this flight can become hazardous and unsafe to do. There are some cliffs at Cape Bird where the helo needs to land, so good visibility is essential. Luckily for us, the skies were mostly clear so we could fly to Cape Bird with ease. The helo pilot even asked me to take some pictures of the area where the flying becomes precarious as he took waypoints to document the surface features.

View of part of the “precarious area” on our way to Cape Bird. This is looking back toward McMurdo. You can see the elevation is steep along the coast, and there is plenty of open water. Mt Erebus is out of view but to the front left.

A huge bonus about coming to Cape Bird is that there is an Adelie penguin rookery there. So I got to see more penguins! There were some roaming on the beach, and we could see lots in the water swimming and jumping into and out of the water, or standing on icebergs. They looked like they were having fun out there!

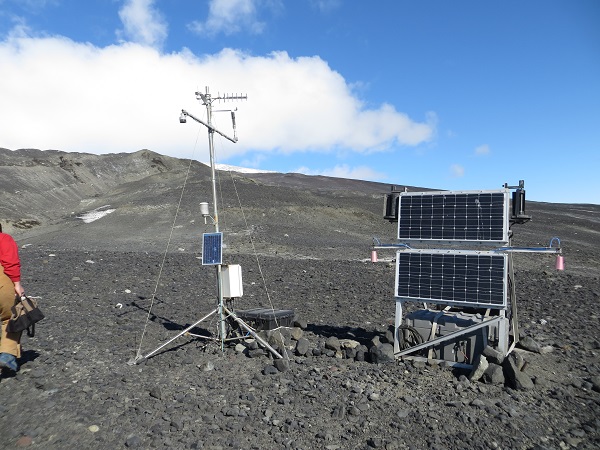

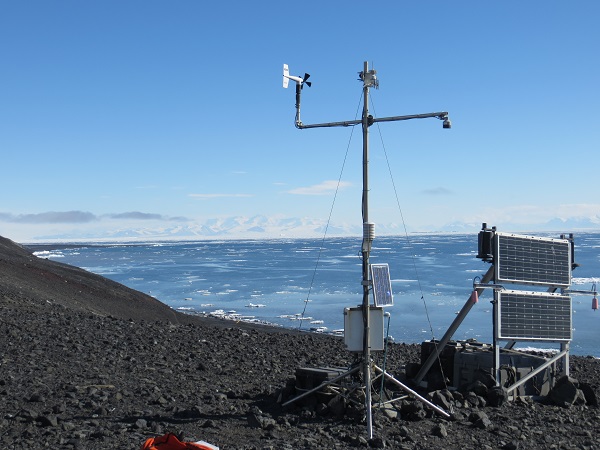

We said hello to some of the Kiwis (New Zealanders) who are stationed at the Kiwi Base there at Cape Bird, then walked up the somewhat steep hill to check on our AWS. Lee and I were anticipating a quick look-around and our work there would be done, but that was an optimistic expectation. At first glance it looked to be ok, but upon closer inspection we noticed the propeller on the anemometer had come completely off, the temperature sensor was missing its radiation shield, and one wing on a wind turbine for Lars Kalnajs’ ozone detection system had broken off.

Right before we departed McMurdo, Lee had the brilliant idea to bring a spare nose cone and propeller for the anemometer, just in case. Turns out we needed it! We got to work on installing that to the anemometer and searched for the missing parts. I stumbled across the broken propeller (it was about 15 feet from the station), but couldn’t find a trace of the radiation shield or broken piece from the wind turbine. We think that high winds picked up some rocks and caused this damage to the station, perhaps taking out all of the broken pieces in one fell swoop, or maybe there were two or three separate instances. There was a fair bit of corrosion on the station due to the sea, but despite these defects we verified that the AWS is still recording and transmitting measurements. The wind speed and direction are back on as well.

We will need to visit this station again to install a new radiation shield for the temperature sensor. Until then, the temperatures it records will be invalid as the sun can shine directly on the sensor, heating it up so the temperature it records is no longer a measurement of the air. The relative humidity sensor has a temperature sensor in it, used to calculate the relative humidity, so that should still be accurate and could be used if needed.

Throughout our visit, I was able to snap some pictures of the penguins and scenery. Here are a few that I took.

An Adelie started walking towards me as I searched for the radiation shield, apparently with complete disregard for where it was going. This skua didn’t like how close the Adelie came to its chick (not pictured)

Cheers!

Dave