On 13 January, the weather was forecasted to be good enough on the coast for us to go to Evans Knoll and Thurston Island. We were very excited at the prospect of getting both of those sites done in one day. For each of the sites, we were hoping to replace the RM Young wind monitor with a Taylor high wind system. The sites are windy places, and the RM Young has had a tough time standing up to the wind for more than a year it seems. We figured we could try installing a high wind system, as these are more robust and have proven themselves worthy in some of our windiest locations (e.g., Manuela, Minna Bluff).

Along for the ride with us came Alex Wernle, a student with the POLENET group. She came with us to help us bring our cargo to the AWS from the Otter, but this trip also functioned as a good way for her to see some cool sights.

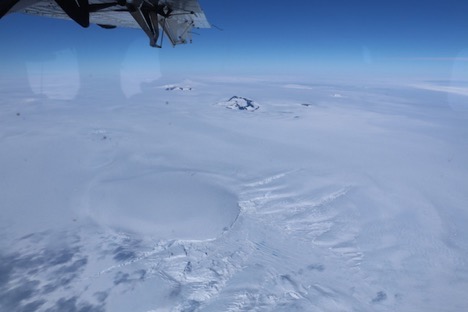

The flight to Evans Knoll and Thurston Island is a long one, with it taking about 2.5 hours to Evans and another hour to Thurston. The flight path to Evans Knoll from WAIS takes from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to the mountains/volcanoes along the coast, where the ice sheets start to flow onto the ocean, calve, and create icebergs. This provides for some really cool scenery.

We also flew by an amazing example of Kelvin-Helmholtz waves, or waves caused by shear between two adjacent layers in the atmosphere. I’ve seen these waves in cloud forms on their own, but never like the following picture, where the waves are at the top of one cloud layer with more clouds above. It is also a really stark example of the wave features that can be created.

It was a bumpy landing when we arrived at Evans Knoll, as it was extremely flat light due to overcast skies. Flat light means that it is extremely difficult to discern surface definition. This is especially hazardous for pilots here in Antarctica because the majority of their landings are in the open ice fields of the continent. Despite the difficulty, the pilots got us on the ground safely and we prepared to hike up the hill to our AWS.

View from the plane of Evans Knoll (background, with some rock exposed on the side of the hill). The cloudy conditions make it almost impossible to see surface features.

Where we de-planed, with the fuel cache in the foreground and our AWS up at the horizon on the hill. It’s the short, dark line between the red flags.

Marian, Alex, and I got all of our gear in hand and began hiking up the hill. It’s a fairly steep hike, so with carrying around 40 pounds of gear each, it can be taxing. Slow and steady is the key. We didn’t make it very far, however, as we hiked about 50 feet up the hill and encountered a crevasse. We hiked back down to discuss our options. It’s very unsafe to hike across a crevasse. Since we didn’t have a mountaineer with us (someone skilled and knowledgeable in basically everything outdoors), nor did we have crevasse training, nor did we have the equipment necessary to make this trek a safe one, we made the decision to abandon the mission. It was an easy decision in terms of safety, but a hard one because the AWS was so close, and we were so close to completing this work. Alas, Antarctica is a harsh continent.

We packed up and headed for Thurston Island to see if we could do the wind sensor swap out there. We flew for about 20 minutes, but the cloud deck only got thicker. We turned around to head back to WAIS after the pilots determined the flat light conditions were not going to get any better. Alas, yet again, it’s a harsh continent. But at least we all made it back safely.

On 16 January, we tried to get to Thurston Island again. The forecast called for scattered cloud cover for the day at Thurston, which would provide enough sunlight to allow the pilots to see the surface definition and features. Marian and I packed our things on the Otter and headed out once again.

It was mostly sunny for most of our flight, so we could see some of the cool ice formations along the way.

Unfortunately, Antarctica is a harsh continent. Shortly after we passed Evans Knoll, the clouds began to thicken. It was a low layer of stratocumulus that just got thicker and wouldn’t budge. We were thinking, what happened to the promised “scattered” clouds? As it was getting to be about the time that we would be at Thurston Island, the cloud layer was as thick as ever. We descended a bit, flying parallel to Thurston Island, to poke our heads under the clouds to see how the surface definition looked. It was the flattest of flat light. No chance of landing safely. So we had to head back to WAIS for a 3.5 hour ride during which we had plenty of time to sulk. At least we had the icescape to try and cheer us up.

Cheers,

Dave Mikolajczyk