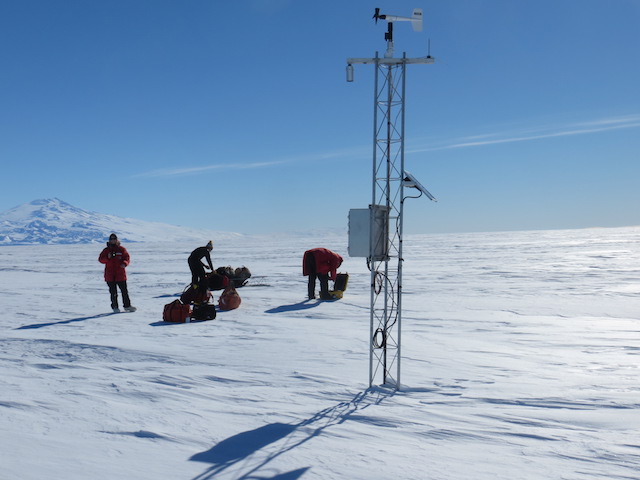

At the end of last week, we had our first AWS site visits of the season. We kicked things off with a helicopter flight to Laurie II on 6 December, with myself, Elina, Mike, and Lee making the journey. Forbes stayed at the lab as there is still some work to be done on the hardware and software for the new PCWS.

Laurie II sits near the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf, just east of Ross Island. The flight to the site is a nice one as we hug Ross Island and get a good view of it and eventually the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf and the open waters of the Ross Sea!

The northern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf, as viewed from the helo. Elina’s head is on the left. The surface conditions were absolutely ideal, borderline hot (haha), at the site. Temperatures hovered around 30F with calm to no wind and sunny skies. No coats were necessary that day, especially after doing some digging to recover the power system.

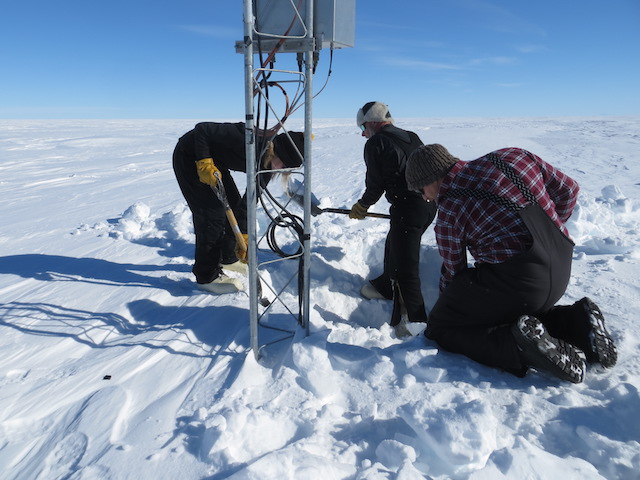

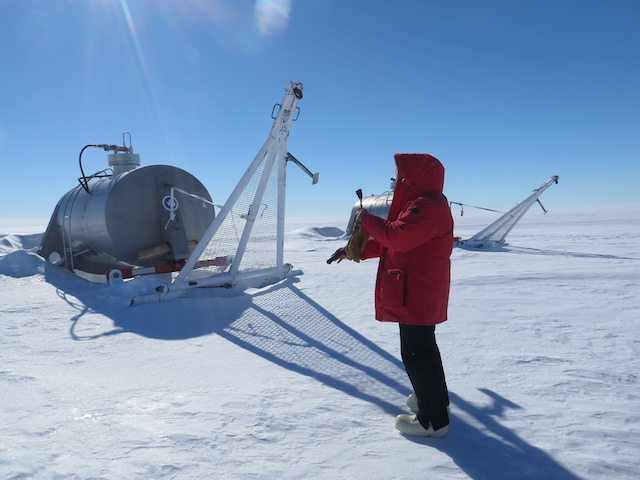

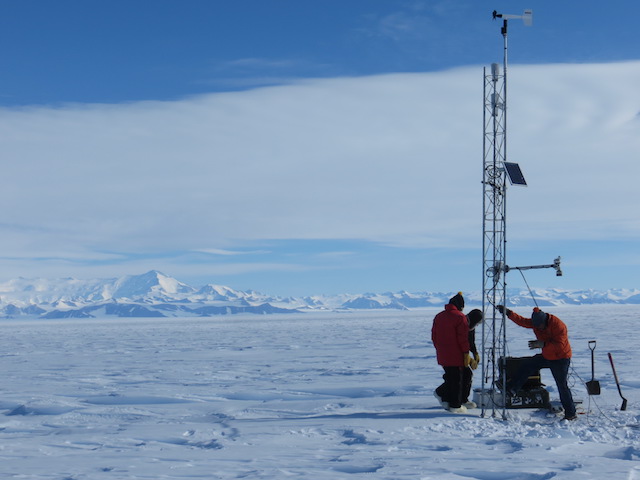

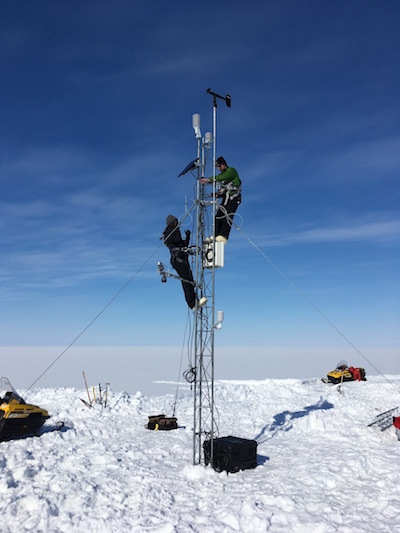

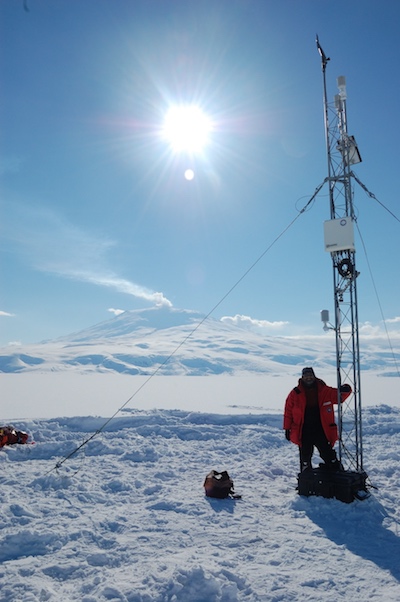

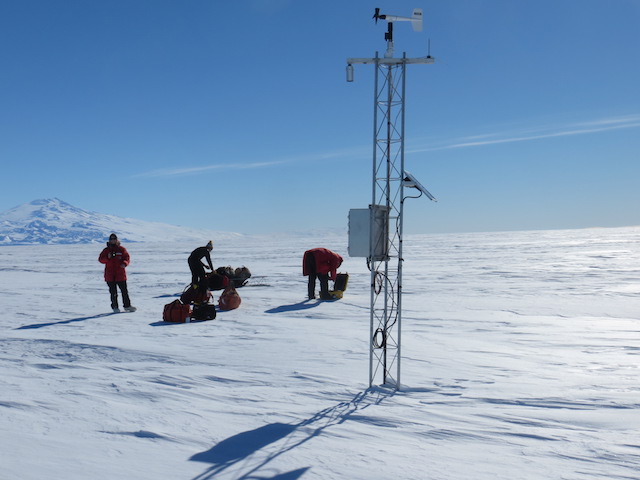

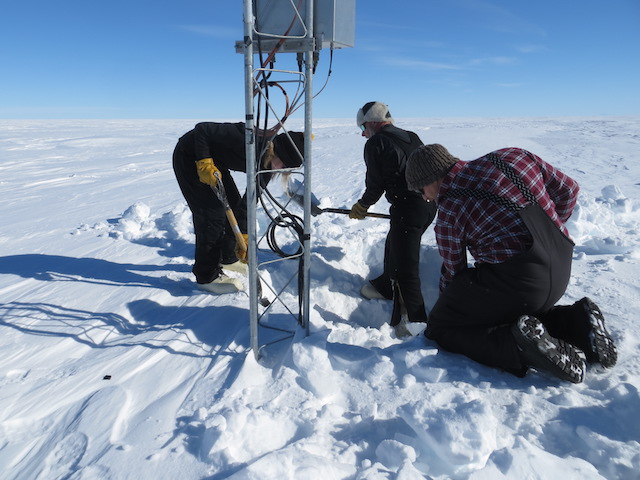

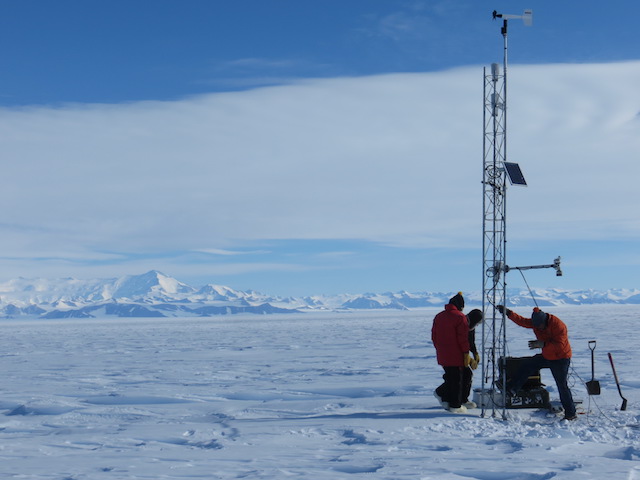

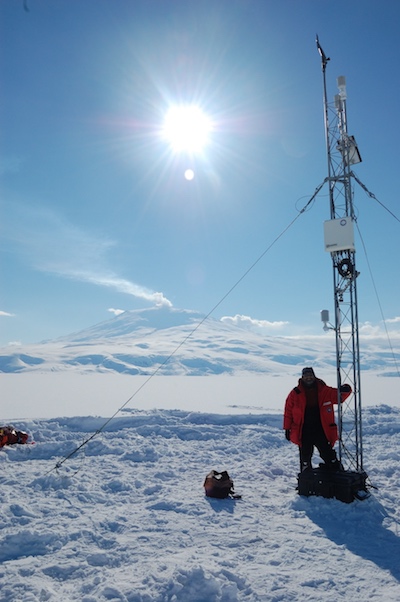

Laurie II upon arrival, with the crew and Mt. Terror in the background.  Digging out the power system.  Lee and I installing the new tower section. (Photo courtesy of Mike Penn)  Elina pointing out where the South Pole is (not pictured). (Thanks for the pic, Mike.)  Done with the raise! Our first site visit was a success, and we looked to continue that the next day with a Twin Otter flight to Sabrina to raise the station. This visit to Sabrina was a long time coming… We spent essentially all of last field season trying to get there but couldn’t, mostly due to poor weather.

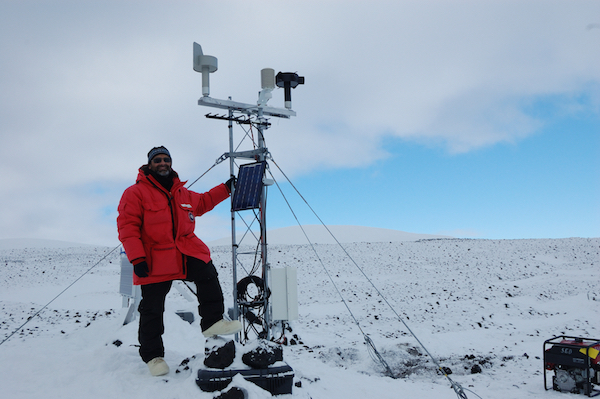

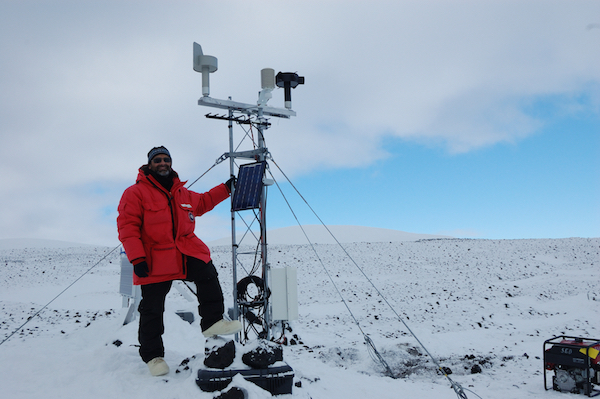

The field team for our visit consisted of me, Elina, Mike, and morale-tripper Dan Garcia, who works in town as a heavy equipment operator. This is Dan’s first time to the ice, and he was very happy to get out in the field with us and willing to help in any way he could. And help he did! It turned out that we needed all four of us to work well to get our work done in time….

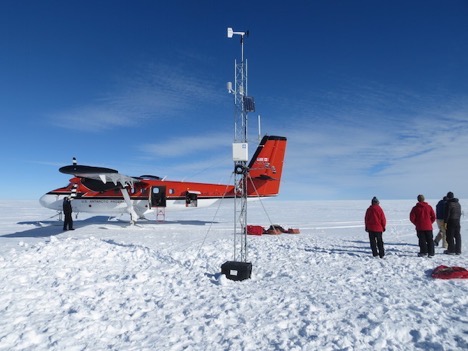

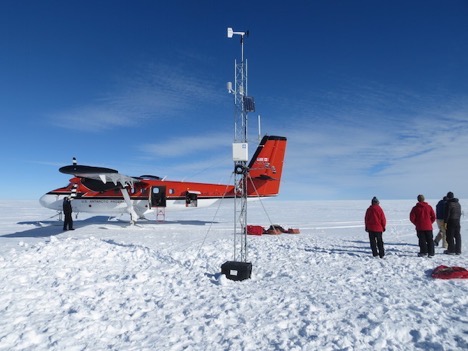

It’s a long flight to Sabrina, approximately 500 miles (800 km) from McMurdo. As such, the Twin Otter needs to stop at a fuel cache along the way to refuel. This of course adds time, and the pilots only have a certain amount of time in a day during which they can work, called their duty day. It starts in the morning when they check weather and lasts for 14 hours, I think.

It took 2 hours 17 minutes to fly from McMurdo to the S+200 fuel cache, then another 1 hour 22 minutes from the fuel cache to landing at Sabrina. There was a strong head wind on the way there, but we made great time flying with the wind on the way back. Flight time from Sabrina to McMurdo was 2 hours 41 minutes.

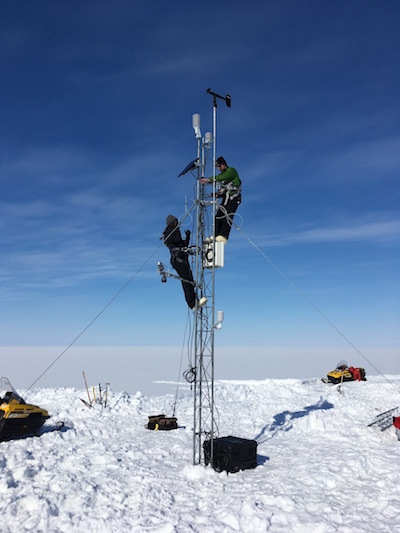

Given this, when we landed at Sabrina, the Otter captain Lindsey said we only have 2 to 2.5 hours of ground time to get our work done. We typically like to allow for 4 hours for a station raise, so this time crunch meant we needed to work efficiently. At the outset, I knew there wasn’t going to be enough time to dig down and recover the power system, so we installed a new one. Perhaps we can revisit this site soon simply to recover the old power system. I thought the field team did great work. We successfully completed the raise in 2 hours 50 minutes. Not too bad!

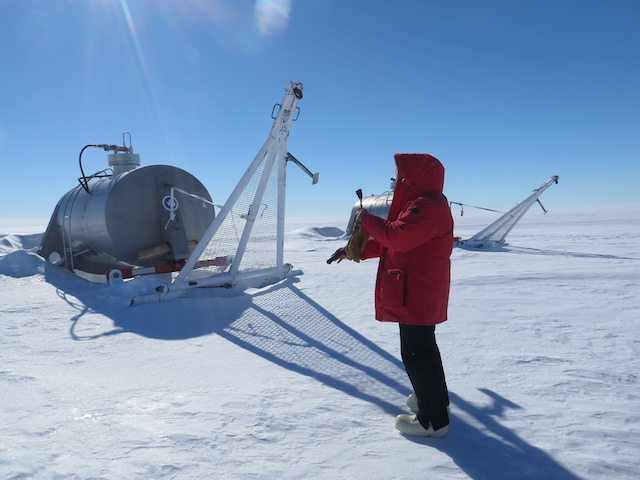

At the S+200 fuel cache, refueling the Otter.  Sabrina upon arrival.  Elina, Mike, and Dan working hard while I take pictures of them.  All done! As I was writing this, we got canceled due to weather to take a helo to Ferrell to raise the station. We had been put on weather hold today, but fog in the vicinity has prevented us from going to Ferrell. Additionally, Lee and Mike were hoping to go to South Pole today, but they’re on a 24-hour weather delay due to poor weather both in McMurdo and I think at Pole as well. Here’s to tomorrow! -Dave

In the time since my last post, we’ve gone to 2 AWS and began preparations for Lee and Mike heading to South Pole and Elina and I going to WAIS! More on that soon…

First, a brief but intense storm came through the McMurdo area on 4 December, bringing strong winds and snow. It got down to Condition 1 at Phoenix Airfield and the Road to Phoenix! I heard that the visibility was 0 at times. It did not get past condition 3 in McMurdo (unfortunately) but the wind was still very strong, creating wisps of wind-driven snow drifts.

Storm with high winds and snow in McMurdo. The buildings in the distance are some of the dorms. The storm left as quickly as it came, and the next day the weather was much improved, much to the pleasure of me and Elina. We had our crevasse training that day that entailed going out to a man-made crevasse to practice our rope techniques, self-arresting, anchoring, and climbing out of the crevasse, among other things.

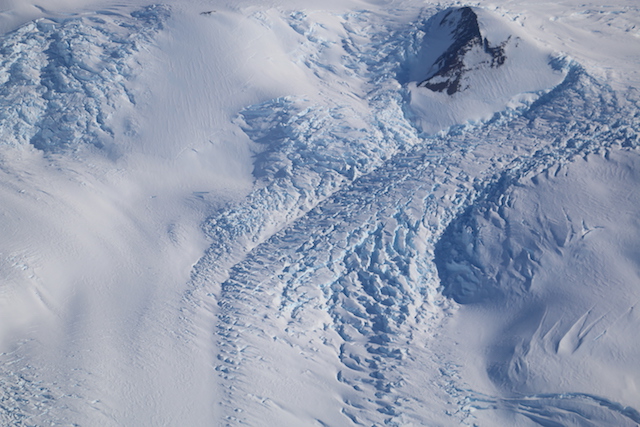

The training began in the classroom as we first went over the basics of how crevasses are formed, where to expect crevasses, and how to walk around or over them. Crevasses form in glaciers when the glaciers undergo stress and strain. Glaciers are large chunks of ice that flow on land, like a frozen river, and when there is a mountain in their way, they flow around that mountain, causing the glacier to bend and eventually “break” or create large cracks, or crevasses. Such breaks can occur when the glacier flows over a slope of land, causing crevassing at the peak of the slope. Crevasses in Antarctica are particularly difficult to navigate through because they usually change rapidly, have a lot of unknown snow bridges, and are in very remote locations where few people have been. “Snow bridges” are when snow accumulates in the crack and can hide the crevasse. Sometimes, the snow bridges are deep and sturdy enough for people (and even heavy equipment) to cross. Other times, they are deceptively weak.

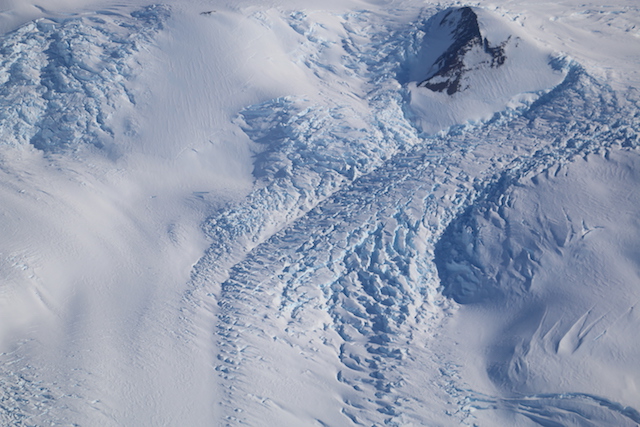

Crevasses in the Transantarctic Mountains as viewed from a Twin Otter ride I took last year. Snow bridges can be seen where there appear to be horizontal stripes in the snow. I don’t think I would want to walk in this crevasse field! When walking near a suspected crevasse field, the team should rope up together, walking in a line, with no fewer than 3 people roped together. Each person has an ice axe in hand and wears a harness to which they can connect the rope, using either a figure-8 knot or a butterfly knot. These knots are useful because they can be tied in the middle of the rope, as opposed to needing one end of the rope. The person in front (who will be the mountaineer AKA expert, in our case) has either an ice axe or a pole to probe the snow surface. If they suspect a crevasse, they will test the snow bridge and determine whether it is safe for us to cross. If so, then it is very important for everyone to walk in the same path. This is because the mountaineer deemed said path as safe to walk on; if we were to deviate even a few feet, the snow bridge may be weaker and we could fall in.

If someone does fall in, there are 7 steps to follow: 1) Arrest the fall. 2) Build a snow anchor. 3) Transfer load. 4) Escape system. 5) Communicate with fallen team member. 6) Prepare the edge of the crevasse. 7) Build a hauling system. The biggest responsibilities for Elina and I, when we’re at Evans Knoll, will be to do steps 1 through 4. The mountaineer should be able to do all 7 steps and get the person out of the crevasse (we can help with the hauling, of course). Nonetheless, we went through all steps for this training to get firsthand experience of what to do.

1) Arresting the fall means, if a team member falls in a crevasse, the rest of the team should pin themselves to the snow as quickly as possible to stop the victim from falling further. We were taught how to properly hold our ice axes and dig into the snow, both with the ice axe and our feet. Once our feet are safely holding us steady, we can 2) build a snow anchor that allow the team members to 3) transfer their load onto the snow anchor so they can 4) escape the system. At this point, the team members can approach the crevasse, while safely hooked to the anchor, to 5) talk with the victim to learn whether they’re hurt and/or able to pull themselves out of the crevasse. Since the rope will dig into the edge of the crevasse, increasing friction and making it more difficult to pull the victim out, we can 6) prepare the edge of the crevasse by inserting an ice axe or something similar beneath the rope at the bend, so the rope slides primarily on the axe instead of digging into the snow. Once the 7) hauling system is in place, all team members can haul the victim out of the crevasse.

If the victim is not hurt and able to pull themselves out of the crevasse, they can do so by using 2 small looped ropes and tie 2 separate Prusik knots. Both of the looped ropes are connected to the main rope, with one connected to the victim’s harness and the other to one of their feet. Prusik knots are created by essentially looping the looped rope over the main rope a few times. When one pulls on the knot, it bends the main rope and increases friction, causing the knot to hold. To loosen the knot, one relieves pressure on it and straightens out the main rope. One can then slide the knot along the main rope with their hand. Given this, the victim will be able to climb up the main rope by first advancing the Prusik knot connected to their harness as far up the rope as they can while pushing on the second Prusik knot connected to their foot. Then they advance the second Prusik knot as far up the rope and ideally to the first Prusik knot, while the first Prusik knot holds because it is supporting the victim’s body weight and bending the rope. They repeat this process and eventually reach the top of the crevasse, at which point they and the field team members can pull them out.

For the second half of our crevasse training, the three of us went to a man-made crevasse just off the snow road to the airfields and on the McMurdo Ice Shelf.

Elina, the pisten bully we rode in, and some of the gear we brought to the crevasse site. The piece on the lower right is our dummy and very brave crevasse victim for the day, Ruth Lee.  The crevasse…. Not much to look at from this angle. The flags mark its location. Upon arrival, we all put on our harnesses and roped up, with me and Elina on the ends of the rope so we could practice arresting in the snow. When it was my turn, Jim and Elina walked and pulled on the rope in one direction, simulating someone falling into a crevasse. I then switch my grip on my ice axe from “walking mode” to “arresting mode”, fell on my belly and dug the ice axe into the snow. I kicked my feet into the snow, trying to get deep enough with my feet and the ice axe to stop from sliding on the surface. Then I could start digging the trench for my snow anchor.

After Elina and I practiced this several times, Jim showed us how to properly dig a trench, set up an anchor, and re-attach to the anchor without worry of anything slipping.

The snow anchor and rope, which leads to the crevasse on the right. Elina and I then roped up, with Ruth Lee on one end. Ruth Lee then decided to investigate the crevasse to see just how deep and wide it was when BAM! She fell in! Elina and I arrested the fall in seconds, stopping Ruth’s fall about 10 feet from the surface. But it wasn’t as difficult as we had anticipated. One thing we didn’t realize was how much friction the rope caused at the edge of the crevasse. We thought Ruth would yank us hard when she fell, but that wasn’t the case. This friction works both ways, of course, so although it helped prevent a great fall into the crevasse, it also means it’s difficult to pull Ruth up to safety. This is where preparing the edge of the crevasse is important. We did so and were able to rescue Ruth. Today she can be found sipping hot tea in the Crary Library, reminiscing on her harrowing experience.

The last thing we did that day was practice climbing out of the crevasse ourselves, utilizing the techniques I outlines above. I think this was the most fun and satisfying part of the training.

Elina (foreground) and Jim, with the two anchored ropes with which Elina and I would practice our escape from the crevasse (and a pretty hefty crevasse it is, right??).  Elina was excited to save herself.  Climbing out of the crevasse!  A full view of the man-made crevasse, with Castle Rock making the picture all artsy in the upper right corner. Elina and I feel ready to conquer Evans Knoll now! We were very appreciative of the opportunity to practice these skills before heading out into the field there.

And as it turns out, I spent way more time on the crevasse training for this post than I thought I would. It is a very interesting subject, and writing this helped me remember some of the details. And now you all know them! Consider yourselves trained… sort of.

I’ll talk about Laurie II and Sabrina in my next post. Cheers! -Dave

The team is (pretty much) all trained up and ready for flying! Over this past week, we have attended training classes to teach us about fire safety, how to sort our trash, how to drive a truck, how to walk around McMurdo safely, and how to survive out in the field. One training that Elina and I will be doing tomorrow is crevasse training. We will utilize this training primarily at Evans Knoll in West Antarctica, if we do indeed go there. I’ll send updates about that in another post.

Elina sitting in our lab.  The view from our lab across McMurdo Sound! That’s Mt Discovery in the distance.  Learning how to make fire in the Field Safety and Training course. Lee and I have also met with the fixed wing (Twin Otter) and helicopter flight coordinators to discuss our flight plans in McMurdo, and at WAIS and South Pole. We all have also gotten our cargo organized, both that we shipped south from Madison and that we’ve left here in McMurdo over winter. All of these preparations led to us being on the flight schedule for the first time today! We were on the Otter schedule to fly to Margaret and Gill, but we were canceled due to weather (which is why I can spend the time to write this). A storm is coming into the area, with high winds and blowing (and some accumulating) snow expected around midday in McMurdo.

Here’s to good weather tomorrow! Cheers. -Dave

P.S. Tug of war! The US and New Zealand faced off, with US women losing 2-1, US men winning 2-1, and US coed winning the only match!

Let the on-ice festivities commence! Hi, I’m Dave Mikolajczyk, and I will be guiding you, dear reader, along for some informative, entertaining, and hopefully never-boring stories that will describe the 2018-19 AWS field season. As it turns out, the story began before you even knew it….

The team arrived in McMurdo yesterday, Tuesday 27 November. We’ve got a full family this year (at least for the first few weeks): myself and Lee Welhouse from UW-Madison, Forbes Filip from Madison Area Technical College (MATC), Elina Valkonen from the University of Colorado-Boulder, and Mike Penn from the PolarTREC program (Polar Teachers and Researchers Exploring and Collaborating). Mike will be on the ice for a few weeks, departing just before Christmas, while the rest of us will be here until early February. Also, Elina and Mike will be writing blogs of their own, and you can follow along with theirs here:

Elina: https://coldspell.home.blog/

Mike: https://www.polartrec.com/expeditions/antarctic-automatic-weather-stations-2018/journals

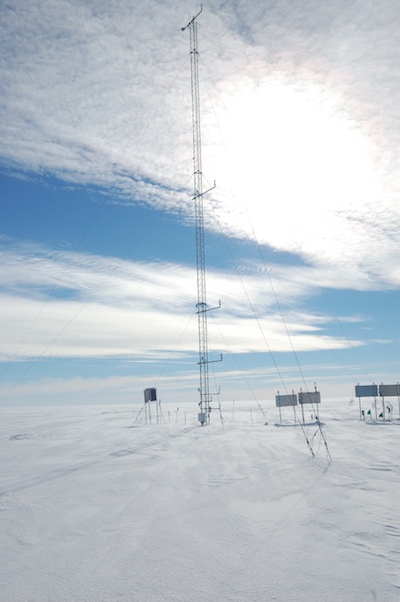

This field season promises to be a busy one, as we will be doing work for several projects. We will be doing the standard servicing and maintenance for the AWS network, with field work out of McMurdo, South Pole, and West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) field camp. For the joint UW-MATC project (for which a test AWS was installed last season at Willie Field) we will be installing 4 Polar Climate and Weather Stations (PCWS), all collocated at existing AWS (except at South Pole). In addition to field work, we will be installing some computer hardware in McMurdo that is used to acquire satellite data.

Lee and Mike will be going in about a week to South Pole to service our 2 AWS and install a new PCWS near the South Pole runway. They plan to spend about a week there doing that field work. Elina and I will be going to WAIS after Christmas, through about 20 January, servicing as many AWS as we can! Otherwise, anyone and everyone who is in McMurdo will be doing site visits around McMurdo and the Ross Ice Shelf.

Before arriving on the ice, we of course came through Christchurch, New Zealand. We arrived in Christchurch on Sunday, 25 November. The following day, we got our completed our orientation and got our cold weather gear at the Clothing Distribution Center. Once all of that was done, we were able to get out and enjoy the city. The weather wasn’t the greatest (temperatures in the 50s F, cloudy, rainy) but it was still pleasant enough to walk around. The sun did peak through at times! I walked through the Botanic Gardens and enjoyed the colorful flowers, good smells, and sounds of wildlife.

A bumblebee and a flower. The next day was flight day. We were originally scheduled to fly on a 757, but the morning of it was switched to a C17. That delayed our departure by a couple hours, but that was OK. It gave us some time to grab a bite to eat, get some last items at the grocery store, and snap this stellar shot of the crew:

The field team. From left to right: Lee, Forbes, Elina, Mike, me. Then we boarded the C17 and headed South for McMurdo! The flight was very smooth with plenty of leg room, which is always welcome on these flights. As we approached McMurdo, the skies cleared and we got some great sights of the sea ice and ice-covered mountains.

The sea ice as viewed from the window.  The ice-covered mountains.  We’re on the ice! That’s all I have for updates right now. We’re hoping to get our trainings done, cargo organized, and be ready to possibly fly this weekend at the earliest, or definitely by early next week. Cheers! -Dave

Hello Everyone!

I have returned from Antarctica. Here’s the last report of what was a very busy last week!!

1. Work continues to the very end!

We continued to work right up to the very end of our deployment. With a break in the weather, we were able to travel to several AWS sites including Alexander Tall Tower! AWS, which is a nearly 100-foot-tall station with 6 levels of weather observing. The station has been slowly getting buried into the snow…its less than 88 feet tall now. Next year we’ll have to raise it up. We also visited Minna Bluff AWS to prevent it from falling over. The rime ice formations there this year have been just tremendous!! The weather station had nearly toppled over with the base of the station nearly kicking out. With some hard work, we now have a well anchored weather station at Minna Bluff, and we even dug out the old anchors for removal next season. On our last day, we finally got some new sensors installed at our testing location at Willie Field AWS and even a new test system installed as well!! It was a busy, busy end of the field season. You can’t leave until you clean up, so we had a full day of packing up our gear, cleaning the lab where we did our work, and we even vacuumed out our dorm room!

Twin Otter parked near Alexander Tall Tower AWS  Alexander Tall Tower AWS  Bell 212 Helo at Minna Bluff  Rime Ice at Minna Bluff AWS  Matthew at Minna Bluff AWS with the new anchoring system 2. Friends

At McMurdo Station, we are always among friends. Beyond a great group of folks to work with throughout the station, I brought a great team with me from Madison College and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. We also found many other folks around the station who are from both schools! Wisconsin has had a great and long-standing tie to the Antarctic. The roots of our project go back many decades as Antarctic meteorology has been an area of study for many years here in Madison.

Madison College friends  UW-Madison friends 3. The Vehicles in Antarctica

I’ve included a series of photos of the transportation means we had access to in Antarctica. There are tracked vehicles, helicopters, fixed-winged aircraft, and many others that are used all around the station. I think the most iconic is Ivan the Terra bus – the main mode of transportation from the airfield to McMurdo Station proper.

Ivan the Terra bus  Delta Dawn  Tracked vehicle  Tracked vehicle  Tucker 4. Chapel of the Snows and Roll Cage Mary

The last Sunday before I left Antarctica, I visited both the Chapel at McMurdo Station as well as a statue of Saint Mary, we affectionately call “Roll Cage Mary”. The Chapel has been a place of worship by many faith traditions over the years as well as a gathering place for other meetings and events. The reason we call the statue of Saint Mary “Roll Cage Mary” is that there is a protective metal grid around it to protect it from ice and rocks that blow around in high wind conditions. This is located on a trail system that has been established around McMurdo Station, where you can hike around.

Chapel of the Snows  Roll Cage Mary 5. Redeployment

After a solid month in Antarctica, it was time to say goodbye. While it was wonderful to be in Antarctica, it is great to get back home and back to family. I have a fisheye lens like photo of the C-17 aircraft I left on. The US Air Force helps out as a part of the US Antarctic Program to move people and cargo to and from Antarctica.

C-17 Thank you all so very much for joining my e-mailing list! I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did!!

Best Regards,

Matthew

It turned out that our attempt to go to Thurston Island on 16 January was our last flying day to an AWS from WAIS for the season. The weather at Thurston didn’t cooperate for the remainder of our stay. The original plan was to have us stay at WAIS until the week of Monday, 22 January. After 16 January, we saw that the forecast for Thurston wasn’t going to clear up for the next few days. On top of that, on Wednesday we heard that a storm was going to hit WAIS for a few days, starting on that Friday. Winds were going to start howling, with a lot of blowing snow and low visibility. Definitely not flying weather. Since we knew we wouldn’t be flying from WAIS over the weekend, knew that we had work to do with Matt and Andy in McMurdo, and had the luxury of “relocating” to McMurdo with the CKB Twin Otter, on Thursday morning, 18 January, we decided that we would leave WAIS.

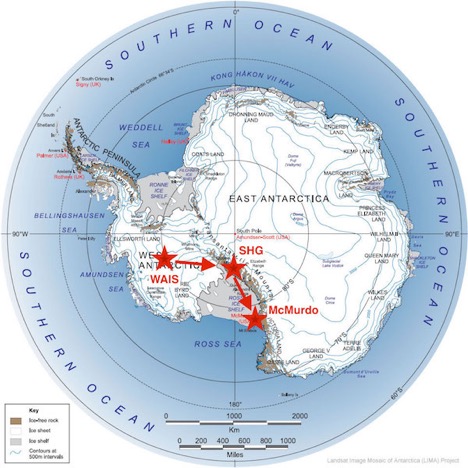

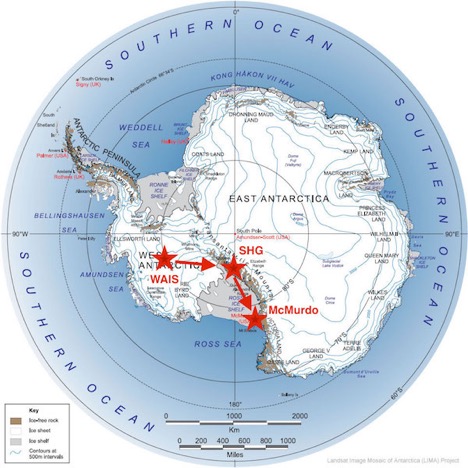

We packed up all of our gear, both personal and work equipment. We cleaned out our tents and had the help of the POLENETters to take down our tents. We packed some food for the flights and departed a little after 9 am. Our route would be from WAIS to Shackleton Glacier Camp (SHG) to refuel, then to McMurdo. SHG is field camp this field season set up in the Transantarctic Mountains, near the southern end of the Ross Ice Shelf.

A map of our flight path from WAIS, to Shackleton Glacier Camp (SHG), then to McMurdo. I say that this was luxurious to leave WAIS by Twin Otter because it pretty much allowed us to leave whenever we wanted. Typically, we would have to wait for a Herc to come from McMurdo to pick us up. Since Hercs are usually in high demand for other missions on the continent, they break often, and they are less flexible than the Otters in terms of flying in poor weather, it is more difficult to leave WAIS on a Herc than an Otter.

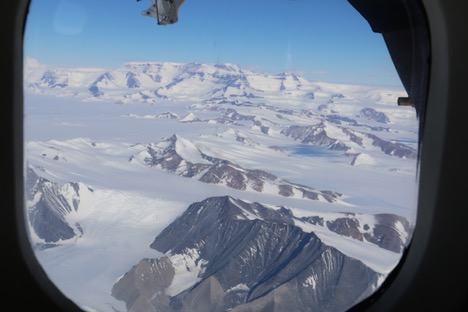

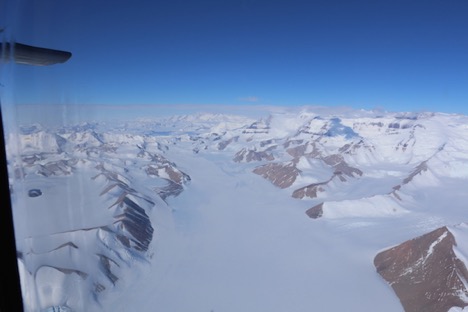

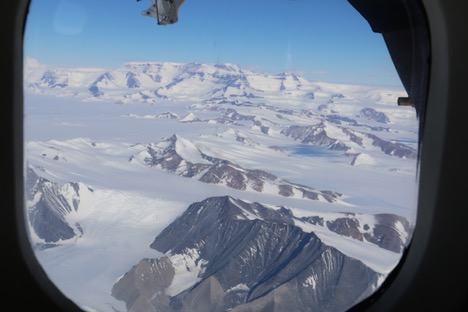

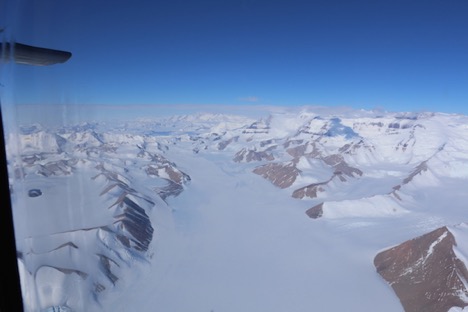

One stipulation about about taking the Otter is that it takes longer to get to McMurdo. The plane is slower, and it needs to stop to refuel. Flight time for a Herc is about 3.5 hours, but for an Otter it was 8 hours, including the pit stop. However, since we flew into the Transantarctics, we got some awesome views, which I’ll show in a bit. The long flight also gave us time to reflect on our stay at WAIS…

Overall, both Marian and I agree that we had a great time at WAIS and wish we could have stayed there longer. The camp staff was awesome. Everyone got along really well, and there was always something to do on the nights. We would typically have a movie night/watch a show in the galley. The chef made delicious food for every meal (we were definitely spoiled in this regard). Playing cribbage was a regular occurrence. Everyone helped out whenever they could, whether it be helping with washing dishes, shoveling snow for the snow melters, or helping camp staff with tasks.

One example was helping Zach organize food we got on a Herc. We spent an afternoon out at the “freezer cave” where the food was stored. We took the food out of the triwalls they were sent in, made an inventory, then helped carry the food down to the cave.

The door to the freezer cave, with the chef Zach in the middle, Marian on the left, and Peter (POLENET) on the right.  The freezer cave.  Cool ice formations on the ceiling. About midway through our stay at the camp, the engineers from both of the Otter crews took a day to make a ski route around camp. There are cross country skis available for use, but no one had ever made a route at WAIS until this year! It was great to get out on a Sunday to get some exercise. It had also been about a year since I skied last… It’s more of a workout than I remember.

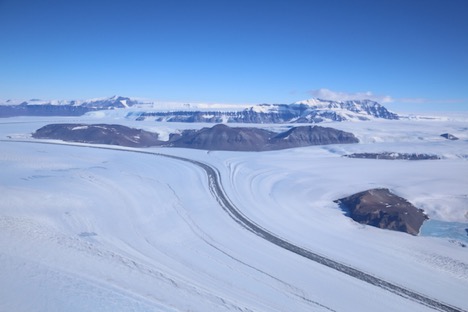

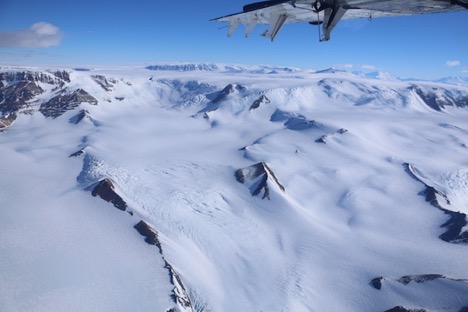

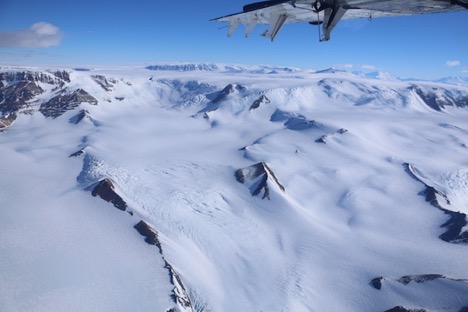

The ski trail went right by Kominko-Slade!  Me and the trail, with tent city to my left and Winterville behind me. So, back to our flight to SHG and McMurdo. After about 3 hours in the air, we started to fly over the mountains. The views were spectacular.

When we landed, we spent about an hour at the camp. It’s a gorgeous camp, surrounded by mountains and glaciers. The weather, according to the people there, all year was pretty much like when we were there: sunny, temperatures around 20 F, and low winds. Very pleasant.

The Otter crew refueled the plane, and we all had some pizza at their camp galley. The chefs knew we were coming, so they made some extra for us (tasty!). We said hi to them (one of which was the WAIS chef when I was there a couple years ago) and some other SHG camp staff (some of which I also met at WAIS a couple years ago [it’s a small continent]).

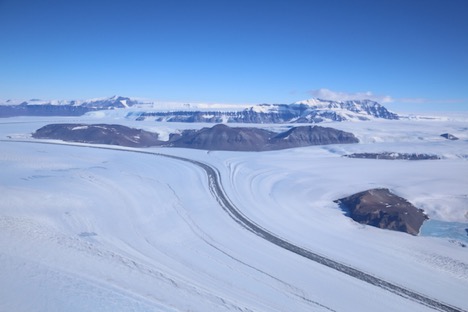

Our Otter on the left, and the SHG Otter on the right.  Looking in the opposite direction as the Otters. In the distance is part of Shackleton Glacier and one of its “steps,” and you may notice the ice falls as the glacier falls down the steep rocky slope. We (reluctantly) departed the camp, McMurdo bound. The sights were just as cool leaving the camp as they were coming in.

A better view of the ice falls, from the plane.  Glaciers meeting

We got back to McMurdo around 5 pm that evening. It was a long day of flying, but we were happy to be back in town to try to get as much work done as we could in our last couple weeks on the ice. And with that, this concludes the WAIS blog posts.

Cheers,

Dave

On 13 January, the weather was forecasted to be good enough on the coast for us to go to Evans Knoll and Thurston Island. We were very excited at the prospect of getting both of those sites done in one day. For each of the sites, we were hoping to replace the RM Young wind monitor with a Taylor high wind system. The sites are windy places, and the RM Young has had a tough time standing up to the wind for more than a year it seems. We figured we could try installing a high wind system, as these are more robust and have proven themselves worthy in some of our windiest locations (e.g., Manuela, Minna Bluff).

Along for the ride with us came Alex Wernle, a student with the POLENET group. She came with us to help us bring our cargo to the AWS from the Otter, but this trip also functioned as a good way for her to see some cool sights.

The flight to Evans Knoll and Thurston Island is a long one, with it taking about 2.5 hours to Evans and another hour to Thurston. The flight path to Evans Knoll from WAIS takes from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to the mountains/volcanoes along the coast, where the ice sheets start to flow onto the ocean, calve, and create icebergs. This provides for some really cool scenery.

Ice sheets and ice bergs, with some open water, along the way to Evans Knoll. We also flew by an amazing example of Kelvin-Helmholtz waves, or waves caused by shear between two adjacent layers in the atmosphere. I’ve seen these waves in cloud forms on their own, but never like the following picture, where the waves are at the top of one cloud layer with more clouds above. It is also a really stark example of the wave features that can be created.

Kelvin-Helmholtz waves in the clouds below the wing of the Otter. It was a bumpy landing when we arrived at Evans Knoll, as it was extremely flat light due to overcast skies. Flat light means that it is extremely difficult to discern surface definition. This is especially hazardous for pilots here in Antarctica because the majority of their landings are in the open ice fields of the continent. Despite the difficulty, the pilots got us on the ground safely and we prepared to hike up the hill to our AWS.

View from the plane of Evans Knoll (background, with some rock exposed on the side of the hill). The cloudy conditions make it almost impossible to see surface features.  Where we de-planed, with the fuel cache in the foreground and our AWS up at the horizon on the hill. It’s the short, dark line between the red flags. Marian, Alex, and I got all of our gear in hand and began hiking up the hill. It’s a fairly steep hike, so with carrying around 40 pounds of gear each, it can be taxing. Slow and steady is the key. We didn’t make it very far, however, as we hiked about 50 feet up the hill and encountered a crevasse. We hiked back down to discuss our options. It’s very unsafe to hike across a crevasse. Since we didn’t have a mountaineer with us (someone skilled and knowledgeable in basically everything outdoors), nor did we have crevasse training, nor did we have the equipment necessary to make this trek a safe one, we made the decision to abandon the mission. It was an easy decision in terms of safety, but a hard one because the AWS was so close, and we were so close to completing this work. Alas, Antarctica is a harsh continent.

We packed up and headed for Thurston Island to see if we could do the wind sensor swap out there. We flew for about 20 minutes, but the cloud deck only got thicker. We turned around to head back to WAIS after the pilots determined the flat light conditions were not going to get any better. Alas, yet again, it’s a harsh continent. But at least we all made it back safely.

On 16 January, we tried to get to Thurston Island again. The forecast called for scattered cloud cover for the day at Thurston, which would provide enough sunlight to allow the pilots to see the surface definition and features. Marian and I packed our things on the Otter and headed out once again.

It was mostly sunny for most of our flight, so we could see some of the cool ice formations along the way.

The icescape along the way.

Unfortunately, Antarctica is a harsh continent. Shortly after we passed Evans Knoll, the clouds began to thicken. It was a low layer of stratocumulus that just got thicker and wouldn’t budge. We were thinking, what happened to the promised “scattered” clouds? As it was getting to be about the time that we would be at Thurston Island, the cloud layer was as thick as ever. We descended a bit, flying parallel to Thurston Island, to poke our heads under the clouds to see how the surface definition looked. It was the flattest of flat light. No chance of landing safely. So we had to head back to WAIS for a 3.5 hour ride during which we had plenty of time to sulk. At least we had the icescape to try and cheer us up.

Cheers,

Dave Mikolajczyk

A couple of weather cancelation days after our dig-out of the Turn 1 fuel cache, we got to another AWS on 11 Jan: Janet. This site hadn’t been visited since 2013 and needed to be raised. We also wanted to replace the power system there because it seemed to be getting a little low on battery voltage at the end of this past winter. Since it had been almost 5 years since it was last visited, we were expecting the power system to be quite buried. It ended up working out that we could bring 4 of the POLENET crew with us to help dig. This made the visit go very smoothly.

Janet is about an hour and a half’s Otter flight away from WAIS. Along the way, we were able to see some mountains in the distance. When we approached Janet, one mountain stood out among the rest: Mt. Sidley. This is also where the rest of the POLENET crew went while we were at Janet.

Mt. Sidley on the horizon as we are approaching a landing at Janet AWS

Janet upon arrival, with the 4 POLETNET crew in the background on the right: Dave, Austin, Peter, and Alex… Those goofballs. As is standard with any raise we do, we first got the heights of the instruments, noted any that were buried, and started digging. Once we dug out the enclosure, I checked that the datalogger was still running, that data looked nominal, removed the data card, and powered down the station. Then Marian and I could free the cables and remove instrumentation while the POLENET crew dug out the power system.

The AWS and POLENET groups working in harmony at Janet, with Mt. Sidley in the background The one thing that gave me trouble with this raise was the pipe on which the aerovane is mounted, one top of the tower. It was quite stuck, and I couldn’t yank it off with either my hands or a big, heavy orange wrench Marian and I affectionately call the murder wrench (think the board game “Clue”) (see picture below).

Me with the murder wrench, trying to remove the aerovane pipe Finally, I got the idea to just hammer the pipe off, using a channel locks tool to grip the tower section and provide more surface area to hammer. It worked! We could put the new 7-foot tower section on.

The new tower section is on! But as this picture indicates, the shovels are always the stars of the show. We finished the work in record time for us this field season (~4 hours), and it was a very satisfying day.

Janet AWS after our raise With the completion of Janet, we were done with all of the AWS raises out of WAIS, and we only had the coastal sites of Evans Knoll and Thurston Island to complete. These last two, however, turned out to give us a lot of trouble…

Cheers,

Dave Mikolajczyk

Hello Everyone!

It has been a busy few days!

1. Automatic Weather Station Work

This week has been a better weather week so we’ve been able to visit a few weather stations! We made a few attempts to get to Windless Bight AWS. This weather station is located near McMurdo Station. It is not something we can land a helicopter at, due to the soft snow surface. So, we have to drive out. The first attempt didn’t work out – the snow at this location was so very soft and very deep! We drove out on a tracked set of vehicles called a Pisten Bully. Another attempt was made by some Antarctic support staff to help us get a new tower installed for our weather station (we didn’t go as we had another AWS to fly to and service!). Hence, we snowmobiled out to the site, and installed the AWS electronics and sensors on the new tower.

Matthew and the Pisten Bully  Matthew on a snowmobile  Dave and Marian installing instruments on the new tower at Windless Bight AWS  Matthew after servicing Windless Bight AWS Windless Bight is one of my favorite places – if you stop moving around, it is a very, very quiet place. There is little wind. (Hence, the snow that falls here sticks around and is very, very soft!) It is also a great spot to view Mt. Erebus – the world’s southern-most active volcano! Right here on Ross Island, where McMurdo Station is located, this volcano isn’t really like ones you might think of in Hawai’i, but more like one with a bit of steam, etc. On this very sunny day, you can see the plume from the top.

Matthew with Mt. Erebus in the background Another AWS we serviced was Elaine AWS – on the Southern Ross Ice Shelf. This station is near the TransAntarctic Mountains, and is a 2 and half hour flight on a twin otter fixed-wing airplane. We refuel part way there, near the Holland Range, then get to find Elaine AWS. These stations on the ice move – as the ice is moving. This makes finding them a bit of a challenge. Luckily, I spotted it, and we had a great day servicing the station.

One question that you may wonder – how do we name our weather stations? Some are named after existing geographical features already named (e.g. White Island, Marble Point, etc.). Others are named for people important in Antarctic meteorology (e.g. Austin, Kathie, Schwerdtfeger, Lettau, etc.) Others are named for those who have supported us (e.g. Marlene, Henry, Kominko-Slade, etc.) or family members…however, none are named for those of us who actually deploy here to work on the project.

2. Climbing Observation Hill – View of McMurdo

This past Sunday, I took a short hike to the top of Observation Hill. This is the large hill that is right next to the station – and roughly separates McMurdo Station (USA) from the New Zealand station, Scott Base. It has a great view of McMurdo and surrounding areas. It is also a famous location – used by the early explorers of Antarctica to watch for returning expeditions to South Pole. One such expedition did not make it back, Sir Robert Falcon Scott’s trek to South Pole in 1912, never did make it back. A cross has been place at the top of the hill in honor of him and his party. It still standing there to this day.

Matthew and Sir Robert Falcon Scott’s cross  Matthew at top Observation Hill 3. Vessel Off load/On load…

The Ocean Giant container ship has been keeping McMurdo busy this past week. In only 2 and half days, the ship was completely unloaded. The ship is already reloaded with items going back to the US. It’s a tremendous job. I keep snapping a photo of the ship now and again (and you can see it in my Ob Hill photo as well). Today the ship left and a refueling vessel has arrived! (I missed a photo of the ship switch…)

The Ocean Giant vessel 4. Freshies!

After a long period of few flights on and off continent, we did not get any “fresh” vegetables or fruits (or even eggs for that matter!). Finally, we got some recently. Some from the Vessel, and even the research vessel….more will be on future flights. We call these “Freshies”. It is so nice to get an apple to enjoy. Eggs are now very popular at breakfast!!

It’s snowing here – photos attached.

More soon!!

Matthew

In the evening of 5 Jan, another Twin Otter came to camp! This one has the call-sign CKB (the first Otter’s call-sign is KBG), with pilots Phil and Tyson. Given the Twin Otter needs for both our group and POLENET, the flight coordinators must have seen the utility in having two planes here. And indeed it is useful!

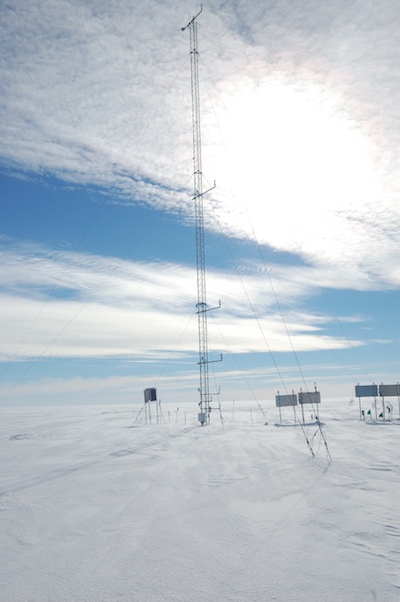

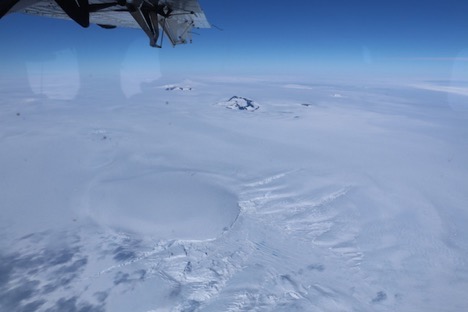

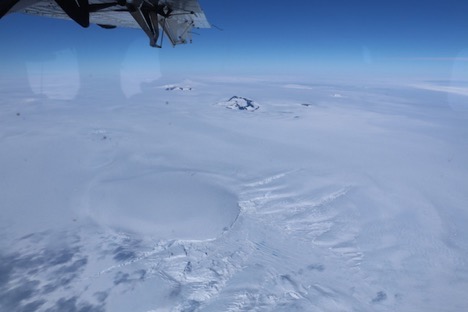

But having two planes is only useful when you can fly somewhere. On 6 Jan, weather was bad everywhere but at WAIS, so there was no flying. Since Marian and I finished our work at Kominko-Slade, we were available to help POLENET with their seismic site they have that’s a 20-minute snowmobile ride away from camp. As we had heard and would soon experience, the POLENET sites are WAY more buried than any of our AWS. A total of 8 of us went to the site on 3 snowmobiles. Given the amount of digging and size of their power systems (more than 10 70-pound batteries compared to our 2!), it’s no wonder POLENET brings so many people to the ice.

The POLENET site near WAIS. We had to raise the solar panel tripod (pictured above on the left) and move that to a flat surface. That was buried about 4 to 5 feet. We also had to raise the seismic sensor which was buried around 12 feet. The pile of snow on the right in the picture above is from the deep pit.

The pit, with Austin and Peter (not pictured) deep in it. They weren’t quite yet to the bottom of the sensor. Helping POLENET out definitely made the digging at our sites seem like nothing comparatively. So that was a positive thing we got out of this trip! A new sense of perspective… Marian and I left once the digging was complete and our services were no longer needed. POLENET successfully raised this site, so they have that going for them, which is nice.

After a day of rest on Sunday, 7 Jan, we were canceled on 8 Jan for our Otter missions to any of our AWS sites due to weather. There is a fuel cache, Turn 1, about an hour’s flight away at which the fuel drums needed to be raised to the surface. Since Marian and I weren’t doing anything else, we offered to fly with CKB to help them dig it out. Terry and Alex from POLENET also came along.

The weather at WAIS was cloudy and dreary, but it was nice and sunny at Turn 1. The wind, however, was fairly strong at around 15 knots when we arrived and only increased throughout our stay. There were 32 drums full of fuel that we were tasked with digging out.

Turn 1 fuel cache upon arrival, with 32 mostly-buried fuel drums. Since the fuel drums are full of fuel, each one weighed about 450 pounds. Our plan was to try to dig them completely out on one side of the drum and then try to have a sort of ramp up to the surface on the other side. Then we would try to yank it up with the help of a couple cargo straps.

Once we were in agreement on our plan of action, the six of us (Marian, Terry, Alex, Phil, Tyson, and myself) began digging. Where else to start?

The first 20 drums. Once we dug out the first line of drums, we cleared the snow off the surface (to the left of the drums in the picture) so we had a good area to place the drums. Then we all assumed our positions to pull the first drum out. Alex and I were in the pit to help push the drum up. Phil and Tyson each had a cargo strap, which Alex and I secured around the fuel drum. Marian and Terry each took the end of the cargo strap and helped Phil and Tyson pull on the fuel drum. We weren’t sure how well it would work, but much to our delight, it worked beautifully. It only took a couple pulls/heaves to get each drum to the surface.

Now the drums are on the surface! We all took a break after the first line of drums. The second line of drums was a little bit more intense because the wind had increased, and blowing snow became a nuisance. Regardless, we got those drums up and finished our work in a couple hours. It was a good workout and pretty satisfying to raise them. They probably have a couple years where they can be neglected before they will need to be raised again… which is representative of just about all field work in Antarctica.

Cheers,

Dave Mikolajczyk

|

|